7 min read

Written by Theresa Schumilas

A storm is brewing, and it is blowing a cold front towards our local food movement. In the past few months, a rash of hatches, thatches and dispatches have begun circulating in localism cyberspace (quite a contradiction in terms) prompted by the release of The Locovore’s Dilemma: In Praise of the 10,000 Mile Diet, by Pierre Desrochers and Hiroko Shimizu.

Engaging with the discussion, Lenore Newman writes, “Is local food at best a silly fad or at worst a dangerous mal-appropriation of resources by a small elite?” Indeed — a question worth thinking about.

Much of the current food localism debate seems focused on contrasting systems that privilege locally grown versus globally traded foods, and in particular Desrochers and Shimizu, attack the movement from a classical economic perspective. (“Is there any other?”, I suspect they would ask.) It is precisely to this preoccupation with oneeconomic system (usually referred to as the market) which I believe local food systems are trying to respond. Critics of diverse food movements (local, organic, fair trade, slow food) seem to have little tolerance for efforts trying to build systems that are based in different ethics.

The local food movement seems to be approaching the point where organics was at in the early 90s. Back then, when a young organic movement was barely out of cloth diapers with a miniscule half of one percent of agriculture land in organic production, academics, bureaucrats, industrialists, media and consumers alike hurled criticisms of “conventionalization” and “mainstreaming” at a movement that was simply trying to reveal the possibility of something other than the dominant, industrial approach to growing food. The movement deserved encouragement not criticism. Indeed stories of “organic lite” popularized in the media turned consumers seeking “anti-corporate” food from organics to local. Ironically, this has hurt our local (and decidedly not corporate) organic producers — the very farmers who built local alternative food markets based on an ethics of care for the environment and for others (both near and far) long before locovore was a word.

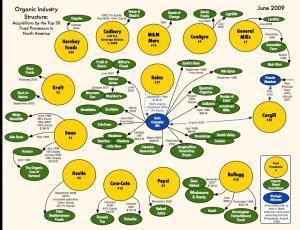

I am not saying that the organic sector has not “mainstreamed”. (Philip Howard’s work on consolidation in North America’s organic sector is fascinating and the visuals are fascinating). For certain, global pressures have affected the organic movement (by the way, SunOpta’s stock was just upgraded from hold to buy if you are interested) but that doesn’t mean (to quote the Borg from Star Trek) that “resistance is futile”. Indeed — perhaps the real question is how and why do new organic CSAs, buying clubs, farms and markets continue to emerge — despite 20 years of global consolidation pressure?

Maybe those of us building the local food movement can learn something from the organic story. We have, after all, no ‘get out of global corporate dominance free card’ and consolidation and

mainstreaming are likewise affecting the local food movement. Consider for example, the Loblaw’s campaign — “Grown Close to Home” in which store layouts are re-designed to make you think you are at a farmers market (the store close to me brings a little farm tractor into the store in the fall and arranges produce around it.) and commercials with Galen Weston chumming around on farms. But in fact, Loblaw’s has only committed to a goal of sourcing less than half of the store’s produce “locally” (defined as grown in Canada) for just 2 months of the year. I’m not sure what they think we locovores do for the other 10 months of the year or for other food groups. While “Grown Close to Home” conjures up images of little organic vegetable farms like mine, in fact the suppliers listed on their website are huge corporate farms, some with operations around the world.

Welcome to ‘local lite’

I think it is our lack of clarity and focus that invites both green washing and critique. Indeed, we “foodies” have big hearts and big dreams. We claim to be the solution to everything. Local food will repair ecological damage, halt climate change and solve peak oil; it will re-connect us with where our food comes from and revitalize local economies; farmers and farm workers will be treated more fairly and traditional farming and food practices will be restored; it will end land grabbing and peasant oppression; it will fix the obesity epidemic and solve our health budget crisis; and it will do all of that, while making food affordable to everyone.

Seriously?

I wonder if our big hearts have blocked some of the synapses from firing in our big heads. Maybe it is time for a little local navel gazing to try to figure out where we want to head with this movement we are building. (Most of our tummies are big enough to withstand it I think). Are we really saving the world by shopping? Or are we, unintentionally, the pawns of larger and perhaps more sinister, global agendas, and maybe even making things worse?

You can’t build a food system on dreams and Desrochers and Shimizu’s criticism of locovores dwelling on romantic ideals and pastoral visions of cute little farms is spot on. If we are revealing new food system possibilities (which I think is what alternative food movements are trying to do) then we need to shape them in directions that are fully baked and thought through. As Lenore Newman so clearly puts it, the local food movement will have to “account for itself” if it is to weather the current storm.

If being forged in the recent fire of criticism is to make us stronger, we have some serious questions to ask ourselves. Does a five minute purchase at the market every couple of weeks really help me to “re-connect” to where my food came from? What makes it different from buying “placeless” food in a grocery store? Do I know anything about where it was grown or who grew or how it was grown? Is it possible that focusing on where food is produced distracts us from the significant environmental consequences of how food is produced? The bulk of produce in our local markets is grown with practices such as fumigating soil, spraying pesticides, and relying on fossil-fuel derived synthetic fertilizers. The Record reported last week that 2 in 3 of our local farms in Waterloo Region applied herbicide to their farmland in 2011. This is greater than the provincial average — where (only) half of Ontario’s farmland has had herbicides applied. Indeed, with only a small (estimates are saying 11% on average) percentage of our food’s carbon footprint coming from transport, our love affair with “food miles” has distracted us from the serious environmental impacts associated with how our 100 mile food is grown.

It seems a bit shocking to think that the Waterloo Region area of the province, which by many accounts has been a driving force behind the “buy local” movement, has farms that are less environmentally aware than other parts of the province. But let’s think about that. Why do we find this so shocking? Did we think that it was only those “bad” farmers from far away who used environmentally harmful practices? So that if we bought produce locally at one of the area’s numerous farmer’s markets we could show our support — “vote with our dollar” — for farmers who demonstrate better stewardship practices?

“Yes, but there are economic and social justice reasons for buying local” you say. That’s true. (Alhough, when people say this to me I always want to ask, “You don’t care about the environment? Really? Do you have somewhere else to live?). Indeed — we should care about BOTH the environment and the people who live in it. So we also need to think about fairness. We need to think about ‘who’ (not just ‘where’ and ‘how’). Who gains and who pays in local food systems? Does buying local improve the lot of the small scale farmers who are fighting against the “go big or go home” mentality of industrial agriculture? How much of our local dollar gets to our local farmer? How inclusive are our local food initiatives to diverse groups of people?

We need to move beyond, what some of our critics are calling, the “cult of localism” which has us blindly seeking local foods without deeper analysis. In short, we need to bring greater clarity to our movement. Where food is produced and procured matters. How food is produced also matters. Who benefits and who pays the costs of our system matters too. Local is where. Organic is how. Fair is who. Let’s have the courage to ask the wicked questions.